The tsunami of 26 December 2004

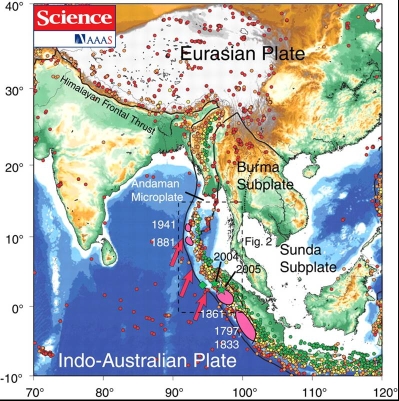

The cause of the tsunami in Sumatra on 26 December 2004 which affected the entire Indian Ocean was a very violent earthquake of magnitude 9.3 on the Richter scale. It was the biggest earthquake ever recorded after the one in Chile on 22 May 1960, with a magnitude of 9.5. It originated at 00:58:53 GMT (7:58:53 AM local time), on a fault in a subduction area between the Indo-Australian plate and the Burma plate (which forms part of the larger Eurasian plate (see fig. 1), with the hypocenter at a depth of about 30 km, 160 km east of Sumatra. The coordinates of the epicentre are: latitude 3° 19' N and longitude 96° E (see green star indicating 2004 in fig. 1). As you can imagine, this a high-risk seismic area.

Fig. 1: Earthquakes with a magnitude greater than 5 from 1965 to 25 December 2004. From the earthquake catalogue of the National Earthquake Information Center (NEIC). The red arrows indicate the shift of the Indo-Australian plate towards the Eurasian plate. (Credit: T. Lay et al., Science AAAS 308, 1127 -1133 (2005)) |

The size of a seaquake depends above all on the extent of the fault on which it occurs and the vertical shift of the sea bed. The fault in question is about 1200 km long (almost as long as Italy), and the shift of the fault varies on average between 5 and 10 metres.

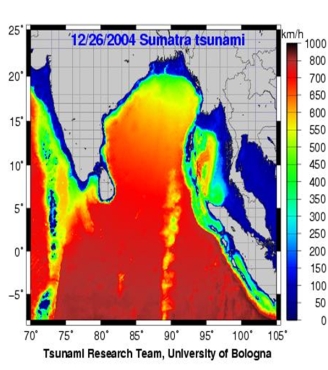

The tsunami took different amounts of time to reach different countries. As we have already said, the speed increases in relation to the depth of the sea, so in deeper waters the wave travelled more quickly. The Tsunami Research Team at Bologna University has calculated how quickly the tsunami propagated (see fig. 2). Areas near the coast are coloured in blue (minimum speed) and areas of open sea are coloured in red (maximum speed) – obviously these latter correspond to the deepest areas of the Indian Ocean.

Fig. 2: Map showing how quickly the tsunami in the Indian Ocean spread. The areas with high speeds are in red, those with lower speeds are in blue. (Credit: Tsunami Research Team, Physics Dept, University of Bologna) |

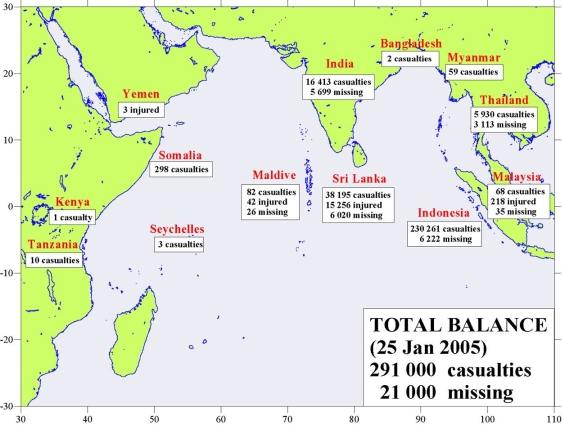

We know that after 15-20 minutes the tsunami had already hit the northern part of the island of Sumatra, after one hour and a half it hit Thailand and after about two hours it had reached the coasts of India and Sri Lanka, causing a total of around 290,000 deaths (see fig. 3). As with all large-scale disasters, the final number of victims will never be known.

|

Fig. 3: Number of victims in the various countries affected by the tsunami of 26 December 2004. |

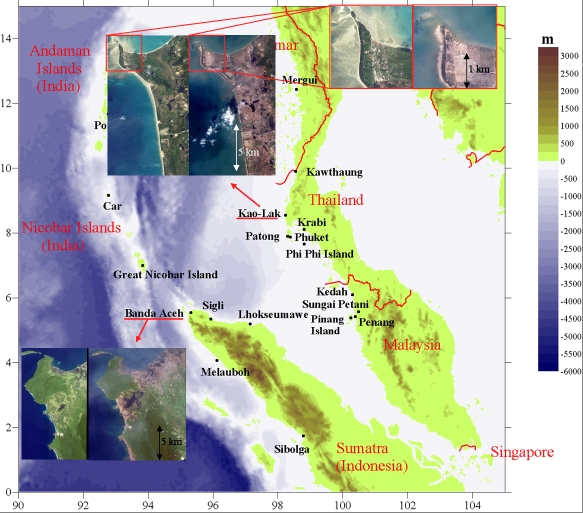

Satellite photos taken before and a few days after the disaster show the destructive effects of the tsunami. In Fig. 4 the towns of Banda Aceh in Sumatra and Kao Lak in Thailand are highlighted; destruction up to several kilometres inland is clearly visible.

|

|

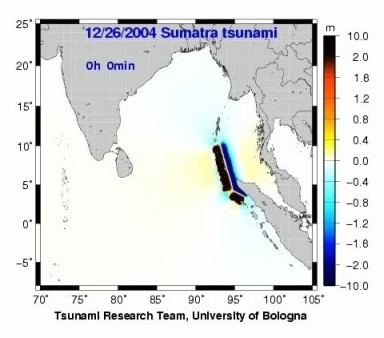

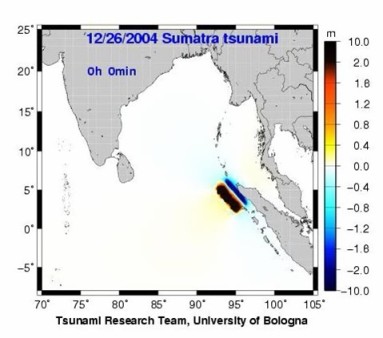

The Tsunami Research Team at Bologna University has developed computer programmes which can simulate tsuanmis produced by earthquakes. As input data, these programmes use the bathymetry of the basin and parameters describing the mechanism of the earthquake. The computer simulations can also be used backwards – we can obtain information on the fault which caused the tsunami by starting from knowledge of its effects. In the case of the Sumatra earthquake, for several days after the event seismologists were unable to ascertain the precise length of the fault. The first calculations seemed to indicate that it could be a fault extending northwards from Sumatra to the Andaman islands, almost 1200 km long (Fig. 5a), or a fault only a few hundred kilometres long, north-west of Sumatra (Fig. 5b). The two faults are very different from each other, as are the tsunamis arising from them. By using the tsunami simulation programmes we realise that the second fault produces a tsunami that is quite different from the one which actually occurred, while the longer fault gives rise to a tsunami more like the one that occurred. We can therefore conclude that the hypothesis of a less widespread fault must be rejected. This conclusion was reached only a few hours after the tsunami, in advance of the seismologists' results.

Fig. 5a: First hypothesis. The fault consists of two segments, with a total length of over 1000 km. (Credit: Tsunami Research Team, Physics Dept, University of Bologna) |

Fig. 5b: Second Hypothesis. One single fault west of Sumatra, approx. 500 km long. (Credit: Tsunami Research Team, Physics Dept, University of Bologna) |

Could the loss of so many lives have been avoided?

This is the question that the whole world was asking.

The answer is that the number of victims would have been a lot lower if

people had been aware of the risks and known about the phenomenon

(like the little girl Tilly), and if an alarm system had been installed in

the Indian Ocean.

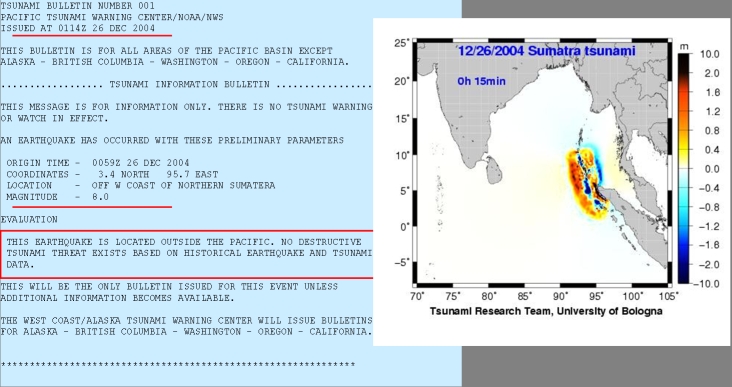

In fact, bulletins regarding a possible tsunami had been issued by the PTWC (Pacific Tsunami Warning Center); as soon as they noted the earthquake they issued two bulletins, 45 minutes apart. The first one, 15 minutes after the earthquake, gave a magnitude less than it really was and did not mention the possibility of a tsunami in the Indian Ocean, even though in the meantime the tsunami had already hit the north of Sumatra and the Nicobar islands. (see Fig. 6a).

Fig. 6a: First PTWC bulletin issued 15 minutes after the earthquake. The simulation

shows that after 15 minutes the coasts of Sumatra and the Nicobar islands had already

been hit by the wave. The bulletin informs that there is no danger of a tsunami.

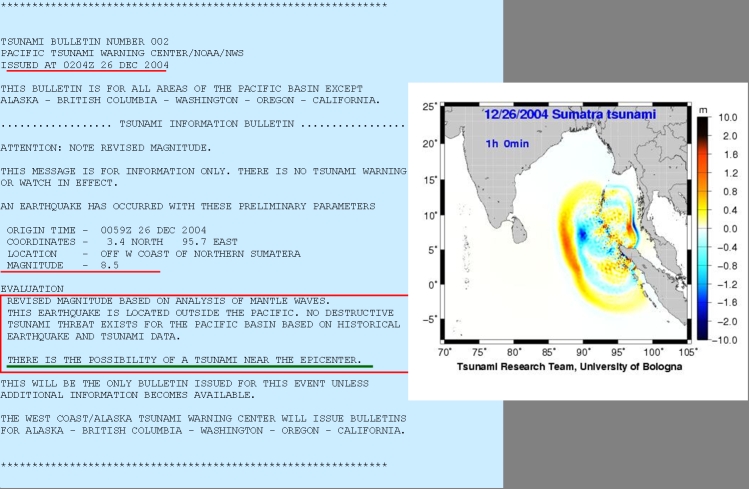

One hour after the earthquake a second bulletin was issued, revising the magnitude of the earthquake and confirming that there was no risk of a tsunami except in the area close to the epicentre (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6b: Second PTWC bulletin issued one hour after the earthquake. The wave is

about to hit the coasts of Thailand and Malaysia. The bulletin warns of the

possibility of a tsunami near the epicentre.

What went wrong?

The PTWC is an alarm system covering almost all the countries of the Indian Ocean. It is made up of a system of seismometers, tide-gauges and buoys positioned in the Indian Ocean. The seismometers give information on the earthquake, while the buoys and the tide-gauges give information on the movement of the level of the sea when the tsunami passes. A big earthquake stimulates seismometers all over the world, so the Sumatra earthquake was detected also by the PTWC seismometer network. However, due to the lack of marine sensors connected to the PTWC in the Indian Ocean, direct data on how the tsunami was spreading never reached the PTWC. Therefore, the PTWC could not inform the inhabitants concerned - this inability to inform was at the root of the catastrophe. Alarm systems are now being installed in the Indian Ocean, so any future tsunami would be identified well before it hit the coasts. It should be noted, however, that it is current practice to issue alarm bulletins 15 to 20 minutes after an earthquake has occurred. If an alarm system of this type had been in operation at the time of the Sumatra earthquake, it would have done nothing to save those people who live in the northern part of Sumatra, as they were hit by the tsunami in fifteen minutes. It was here that 4/5ths of the victims (about 240,000) died.